California’s Transitional Kindergarten Expansion Faces Urgent Teacher Shortages and Equity Challenges

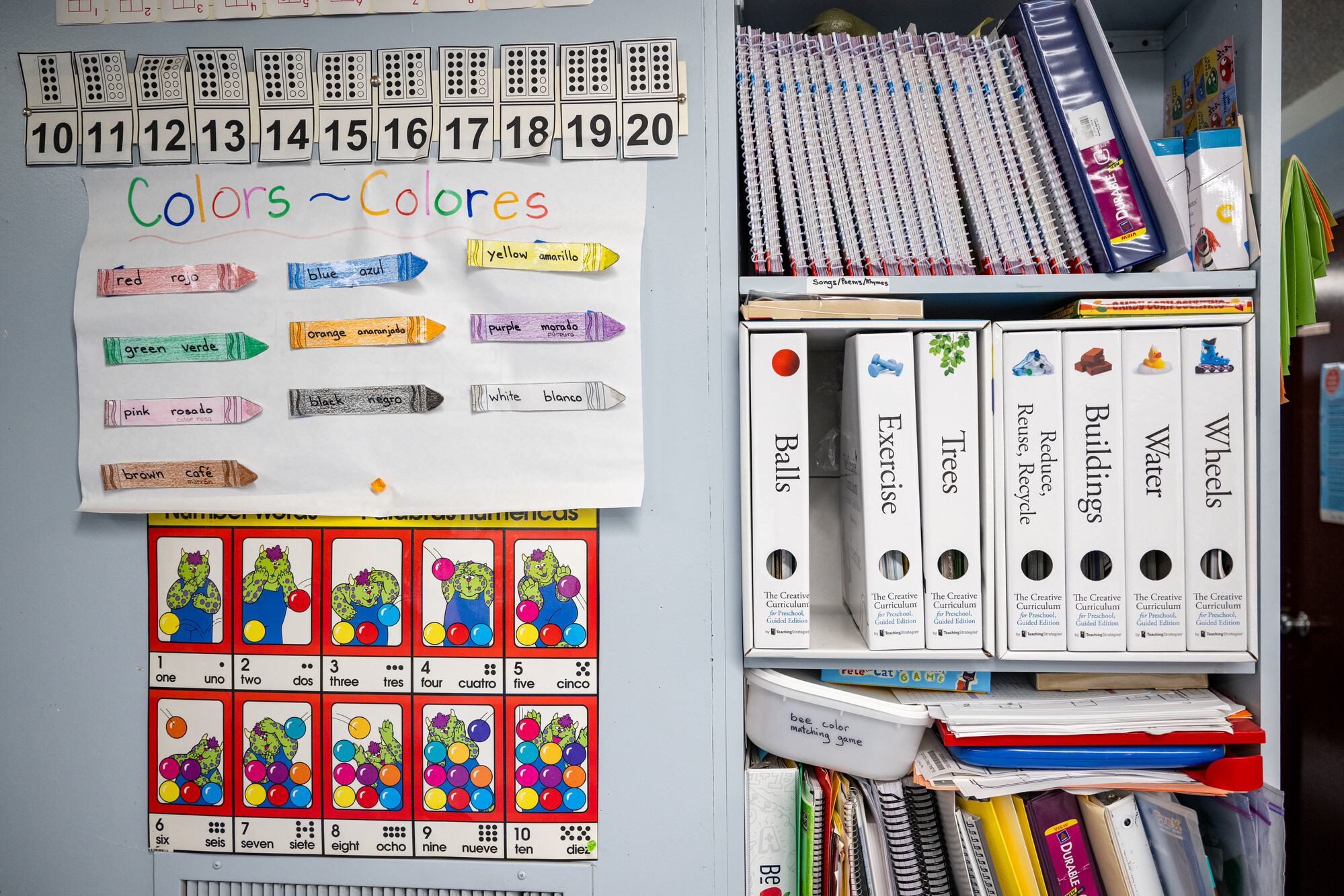

As California races to complete one of its most ambitious educational reforms—expanding universal transitional kindergarten (TK) for every 4-year-old—the state is confronted by a mounting teacher shortage and persistent barriers that threaten the promise of early learning for its most vulnerable children. With the number of TK students doubling since 2021 and a four-year universal rollout entering its final phase this fall, the stakes could not be higher for families, schools, and policymakers across the Golden State.

For parents like Humberto Estratalán, the transition has been personal and fraught. Last year, after enrolling his 4-year-old daughter in TK in the Coachella Valley, Estratalán found her in a class of 30 with only one teacher and no dedicated aide—a far cry from the state's rule of one adult for every 12 students. When his daughter was left to change herself after an accident because no staff could spare the time, it was "the last straw." His push for more oversight convinced the district to hire additional staff, transforming his daughter’s school experience overnight. His story is echoed across California as districts—especially those in rural and high-poverty areas—scramble to hire enough qualified educators amid a statewide shortfall.

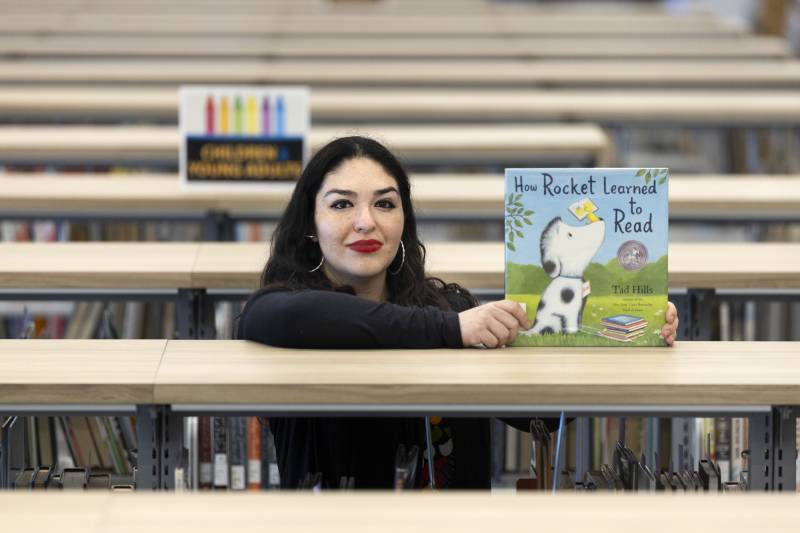

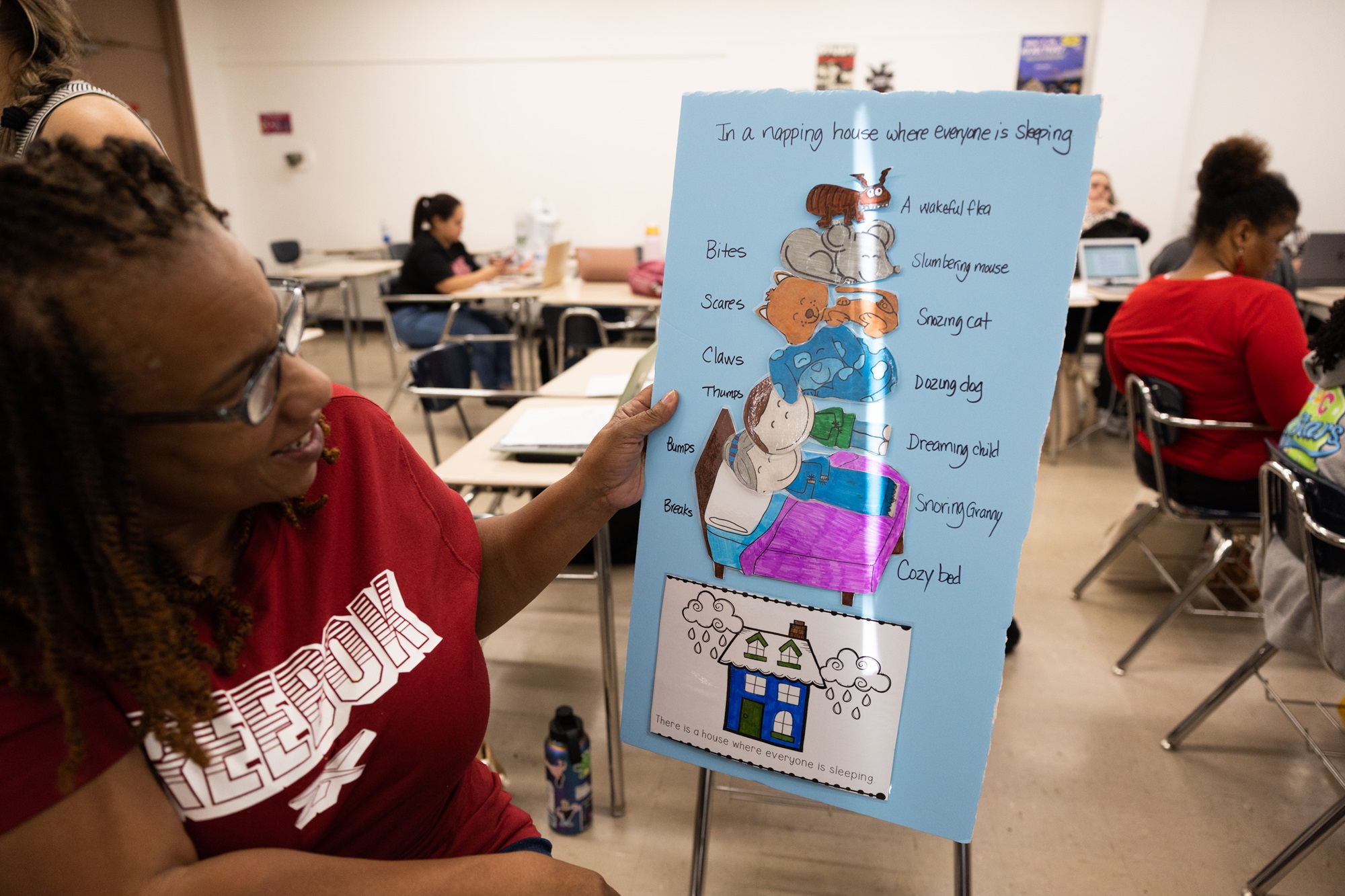

The teacher pipeline problem is deeply rooted in the state’s complex credentialing system. Although thousands of experienced preschool teachers are eager to fill new TK classrooms, the stringent requirements for the new PK–3 credential—including up to 600 hours of unpaid training—often make the leap unaffordable, especially for women of color, who make up the majority of California’s early educators. As Angelica Cardenas, a master’s degree educator with 13 years of experience, laments, "It saddens me that after all the years of education that I have, all the years of experience, I wouldn't be able to teach TK even though that's my jam."

Ironically, public school teachers with little experience in early childhood can move to TK with less training than veteran preschool teachers. While the state offers millions in grants and tuition waivers to entice candidates, critics argue more action is needed. Lea Austin of UC Berkeley's Center for the Study of Child Care Employment calls the system “inequitable,” noting that preschool teachers—who earn less than half the hourly wage of elementary educators—are required to make the largest sacrifices.

Meanwhile, the demand for TK has surged. Statewide enrollment has leapt 101% since 2021–22, now covering nearly 60% of eligible 4-year-olds. Growth is especially strong in schools serving low-income families and communities of color—groups historically underrepresented in quality early education. Still, there are signs of emerging disparities: while low-income enrollment numbers are up, high-poverty schools are seeing slower percentage growth compared to their wealthier counterparts, indicating that access barriers persist despite expansion efforts.

Governor Gavin Newsom’s proposed $3.9 billion boost for the coming year aims to shrink student-teacher ratios further and keep TK on schedule, but success hinges on attracting and retaining qualified educators. Mary Vixie Sandy, head of the state’s credentialing commission, acknowledges both the progress and the hurdles: “We're not trying to keep a workforce out, not at all. We most certainly want the workforce in.”

As California marches toward its vision of universal early education, the question remains: Can the state balance rigor with equity to ensure every TK classroom is led by a skilled teacher who reflects and supports the children most in need? The answer may decide whether this education revolution truly gives every child a fair start—especially those who need it most. What do you think? Share your thoughts below.